|

At Stratford in the 70's, the text was all! And there, for the

first time, I tackled the problem of how to speak it. I had three

mentors - John Barton, again; Trevor Nunn,

another Cambridge friend; and Cicely Berry, the voice coach for the

Royal Shakespeare Company. Cis is small and shy, yet she radiates the

energy of a healer, as she lays her hands on your back, your ribs, your

neck, your forehead, soothing the body so that it can breathe freely and

confidently. She encourages the voice to express your individuality and

be responsive to the character you are playing. Your diaphragm muscle

below the lungs, pumps air from the body's centre, guiding it up over

the vocal chords, its passage hindered by nothing but your emotion, so

that feeling and sound are projected as one, over the lips, to sail

along the air, where they strike the audience's eardrums. Cis teaches

the intimacy of acting, regardless of the size of the auditorium. Actors

and audience should be physically connected — that's why I hate the

mechanical aids of microphone and loudspeakers.

John

Barton's lessons are different but equally illuminating. He gets

together half- a-dozen actors, who singly learn a Shakespeare sonnet and

present it out loud to the rest of the group. It becomes a

self-contained speech, without any context of scene or play to

complicate matters. John then analyses it into the ground, whence, if

you're lucky, it grows, nurtured by his knowledge of the myriad devices

and flexibility of Shakespeare's poetry. When it comes to blank verse,

he is omniscient and it took him nine hour-long television programmes

(PLAYING SHAKESPEARE) to say the half of it. It was astonishing how few

of my colleagues at Stratford had time for the Barton classes. They

believed, perhaps, his reputation as a purely academic director.

Rubbish. John Barton is Mr. Show Biz. If a speech or scene isn't working

on its own in one of his productions, he will happily shove a bit of

atmospheric music underneath. He loves sound effects and smoke and dry

ice and elaborate scenery. When I came to do

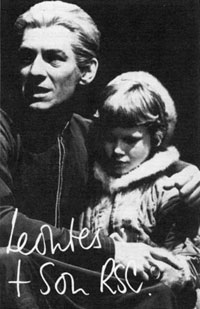

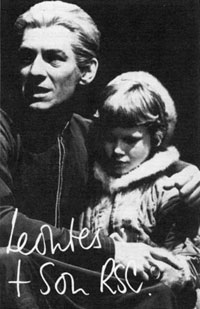

THE WINTER'S TALE with him, I found that the notoriously complex

text had had all the difficult lines cut out of it. I was playing

Leontes and, benefitting from my classwork, I did my newly-trained best.

For reasons never explained, the production had three directors, who

divided up the scenes between them for rehearsing. I cannot invent a

metaphor ridiculous enough to describe the confusion this caused. The

play was botched. John

Barton's lessons are different but equally illuminating. He gets

together half- a-dozen actors, who singly learn a Shakespeare sonnet and

present it out loud to the rest of the group. It becomes a

self-contained speech, without any context of scene or play to

complicate matters. John then analyses it into the ground, whence, if

you're lucky, it grows, nurtured by his knowledge of the myriad devices

and flexibility of Shakespeare's poetry. When it comes to blank verse,

he is omniscient and it took him nine hour-long television programmes

(PLAYING SHAKESPEARE) to say the half of it. It was astonishing how few

of my colleagues at Stratford had time for the Barton classes. They

believed, perhaps, his reputation as a purely academic director.

Rubbish. John Barton is Mr. Show Biz. If a speech or scene isn't working

on its own in one of his productions, he will happily shove a bit of

atmospheric music underneath. He loves sound effects and smoke and dry

ice and elaborate scenery. When I came to do

THE WINTER'S TALE with him, I found that the notoriously complex

text had had all the difficult lines cut out of it. I was playing

Leontes and, benefitting from my classwork, I did my newly-trained best.

For reasons never explained, the production had three directors, who

divided up the scenes between them for rehearsing. I cannot invent a

metaphor ridiculous enough to describe the confusion this caused. The

play was botched.

|